- Interview for U Multicultural Channel

- 2021 Update from the Archives

- Final years of David Hamm (1822-1894)

- Retired church workers archive MC Canada history

- A New Home in Canada: A Virtual Lecture

- A New Look at an Old Diary

- ‘The past always has something to say’

- The Move to Mexico and Paraguay: A Call for Materials

- New MCC Archivist

- Royden Loewen: Farmer, Historian, Storyteller

- Mennonite Heritage Archives part of groundbreaking storytelling project

Interview for U Multicultural Channel

Manitoba’s new multicultural news platform U Multicultural (https://u-channel.ca) interviews archivist Conrad Stoesz to learn about the Mennonite Heritage Archives and the history of Mennonites in Manitoba.

Listen to the interview now:

U Talk S2E34 Mennonite Heritage Archives

2021 Update from the Archives

During the pandemic many people relied on online resources in a new, concentrated way. From the archives, we saw people having more time to do research and asking for access to our archival materials, often in digital format. We are now on the cusp of creating a new Digital Collections project which will provide a new level of access to materials. First to be posted will be community published works such as newspapers, magazines, and yearbooks. PeaceWorks Technology Solutions has been contracted to create this platform.

Our goal is to raise $30,000 to build the infrastructure but hosting all the digitized content is an ongoing cost. As more material is digitized and made available, hosting and access costs will increase by an estimated $800 per terabyte each year.

Imagine the kind of family and community research you could do from home searching community newspapers, letters, and diaries; or the insights you could gain looking at issues the church dealt with as recorded in annual yearbooks. These resources not only allow us to know the “who, what, why, and where,” but can open up our imagination to life in the past and better understand people, forces, and issues. As more materials are posted the potential grows exponentially.

We are excited about this new tool but it is a new and ongoing cost above our regular operations.

We are already preparing materials to post on the new Digital Collections platform! We are excited by this project and the new research that it will enable.

SEE MORE

In addition to the new Digital Collections project, here are a few other things we have been working on. This past year we have had many upgrades to our air handling unit and our building. We have been adding 50 books a month to the Mennonite Historical Library at CMU. We have been active on social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, sharing stories, offering resources, and giving people glimpses into the work of the archives. We were pleased to learn that two books that used extensive MHA resources were honoured with the Association for Manitoba Archives’ Manitoba Day Award (Be it Resolved: Anabaptists & Partners Coalitions Advocate for Indigenous Justice, 1966-2020 and Mennonite Village Photography: Views from Manitoba 1890-1940).

We have received a number of new archival collections, processed materials, created and updated databases and finding aids. We produced another 4 issues of the Mennonite Historian magazine this year together with the Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies. The magazine is in its 47th year of publication and is sent to individual subscribers and most MC Canada, MB, EMC, and EMMC congregations in Canada. We have digitized 450 audio cassettes this year, and outsourced the digitization of several films and reel-to-reel recordings from the N.J. Neufeld and Helen Martens collections. Thanks to a number of volunteers we have posted several translated books and diaries on our website.

MHA was featured in round two of TourMagination’s museum and archives virtual tour; the video has been well received. Conrad also hosted a forum on race relations as part of Anabaptist History Today’s webinar series, and was a guest speaker as part of Mennonite Heritage Village’s “Mennonites at War” exposition. MHA materials and expertise were visible in public lectures such as MCC at 100 conference, Centre for Transnational Mennonite Studies on the Russlaender experience, and publications such as Preservings, MCC’s Intersections, and Roy Loewen’s new book Mennonite Farmers.

SEE LESS

Final years of David Hamm (1822-1894)

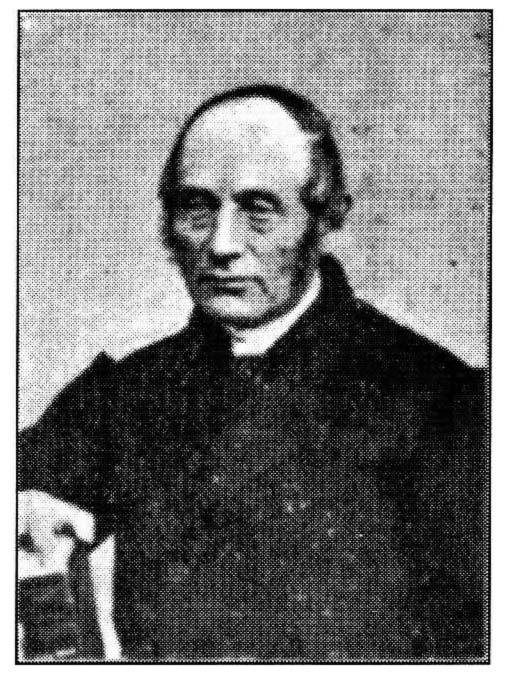

Hymnal compiler and bishop

Edited and adapted by Alf Redekopp from GAMEO

David Hamm was born in 4 October 1822 in Ladekop, Prussia as the son of Jacob Hamm (1788-1851) and Anna (Klaassen) Hamm (1788-1856). In June 1852 he married Anna Hamm (1825-1883), daughter of Michael Hamm (1790-1862) and Helena (Klaassen) Hamm (1898-1866). David and Anna immigrated to Russia from Prussia by 1853 and settled in the village of Hahnsau in the Am Trakt settlement in 1854. He was elected as minister for the Köppental–Orloff Mennonite Church, Am Trakt settlement, Samara, in 1853 and served as bishop (elder) from 1858 to 1884.

During Hamm’s leadership the congregation was greatly disturbed by the activities of Claas Epp, Jr. When Epp published his Die entsiegelte Weissagung des Propheten Daniel und die Deutung der Offenbarung Jesu Christi, Hamm wrote the preface (1877) emphasizing the second coming of Christ, at which time He would find only “a little flock” of faithful followers. He states that Epp was “compelled by the spirit of God” to write this book. However, when Claas Epp, Jr., became more and more extreme in his proclamations the sounder elements of the congregation under the leadership of Hamm opposed Epp’s views.

David Hamm was instrumental in establishing the Allgemeine Mennonitische Bundes/Konferenz, for which he preached a much-appreciated conference sermon at Halbstadt in 1883 proclaiming the motto of the conference based on I Thessalonians 5:12-15 as being “Unity in major issues, freedom in minor questions, and charity in everything.”

SEE MORE

There are also early examples of Hamm’s leadership. In 1869 the Köppental and Alexandertal congregations of Samara sent letters to the Prussian congregation stating that they could not have fellowship with those that accepted the edict providing for noncombatant service. It is likely that David Hamm took the initiative in this matter.

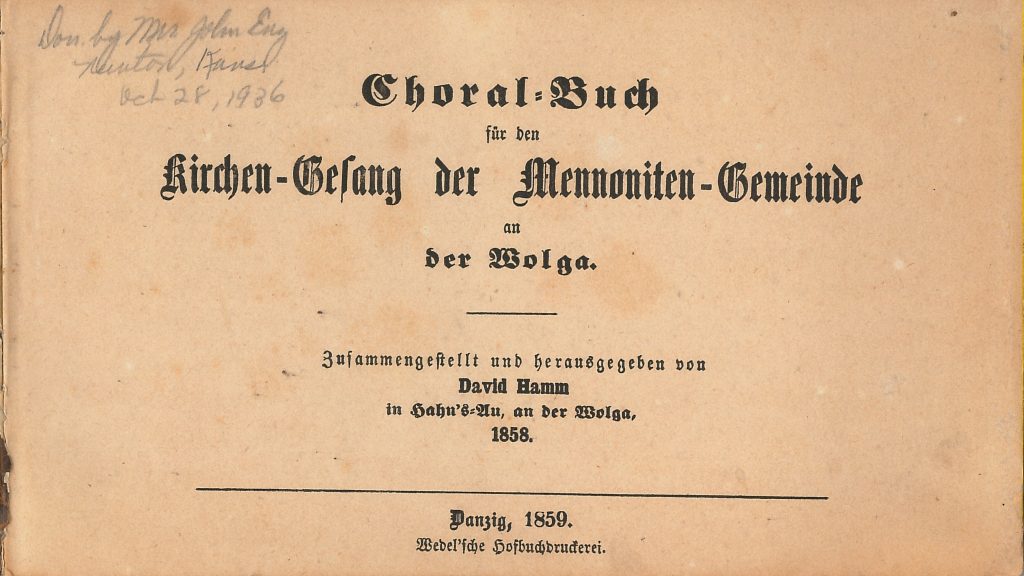

Also early in his ministry, he had a significant influence on the developing of choral singing in the church as the compiler of the Choral-Buch für den Kirchen-Gesang der Mennoniten-Gemeinde an der Wolga. Danzig, 1859.

However, David Hamm’s ministerial leadership came to an end in 1884 when he was removed from office by the congregation and Johann Quiring was elected to replace him. (Earlier historical writings only reported on Johann Quiring’s election and leadership, but nothing more about Hamm.) What happened in the final 10 years of Hamm’s life? Details can be found in the Johannes Dietrich Dyck diary housed at the Mennonite Heritage Archives. (See article by Alf Redekopp, “A New Look at an Old Diary” elsewhere in this issue.)

A few months after David Hamm’s wife died, there was a report that he and a J. Klassen had been on a pleasure trip to Moscow and St. Petersburg, where they had been lured into playing cards and had lost 175 rubles. About the same time, a rumour was spreading that David Hamm had had an affair with the church caretaker’s daughter. Hamm confessed the card playing incident to the congregation on 24 July 1883, but denied that there was anything inappropriate between him and Anna Krueger. Several months later in December 1884, Hamm announced to the ministerial, that he intended to marry Anna Krueger in the near future. There was truth to the rumour he had earlier denied. Having lost faith in his leadership, the congregation elected Johann Quiring as his successor as elder in June 1884.

After David Hamm’s marriage to the young 20-year old Anna Krueger (1864-1889) on 14 June 1884, they are said to have lived in the teacher’s house for a time, implying that he may have had the role of village school teacher for a while. The marriage produced 3 children, of which only the first one survived to adulthood, and the youngest died in July 1889 two weeks before his wife Anna died.

In December 1890, it was reported that David Hamm was boarding with a widow J. Harms, was “horribly addicted to morphine, had forgotten how to wash and comb himself, and that his room was so filthy and dirty at times that it was unfit for human habitation.”

David Hamm died 2 March 1894 — a sad ending to a life that contributed so significantly at an earlier time.

SEE LESS

Retired church workers archive MC Canada history

By Nicolien Klassen-Wiebe, Manitoba Correspondent, Canadian Mennonite

November 3, 2021

Thousands of files languish in the basement of Mennonite Church Canada’s Winnipeg office, holding decades of history but forgotten by many. Irene and Jack Suderman are bringing these records to light, reviewing and organizing them to be stored in the Mennonite Heritage Archives (MHA).

The Sudermans live in Ontario, where they attend First Mennonite Church in Kitchener, but they came all the way to Winnipeg to participate in the two-month project. Since Sept. 30, the couple has been moving materials from filing cabinets to boxes, from binders to folders, sorting, labelling and summarizing the contents.

The key is to organize the files according to the administrative structure of the organization, Jack says. As former general secretary of MC Canada, his knowledge of the system assisted the process.

“When a system is under stress, the first thing that suffers is record keeping,” says Conrad Stoesz, archivist at the MHA, who is working with the Sudermans on the project. When MC Canada underwent a major downsizing in 2017, many staff didn’t have time to clean up their files, which were added to decades of other unprocessed records, he says.

SEE MORE

It is a huge project and it would take Stoesz years to work through the records in addition to his regular workload. The archivist is grateful to the Sudermans for volunteering their time. Jack and Irene have worked in the Mennonite church for almost all of the 56 years they have been married, so they come to the task with extensive knowledge of the church’s inner workings. In addition to Jack working in conference leadership, they served with the General Conference’s Commission on Overseas Mission in South and Central America between 1980 and 1996. In 2017, they did a similar archival project with Mennonite Central Committee Bolivia.

Despite their familiarity with church history, they are learning new things with each box they open. The other day, Jack unearthed a complete hand-written Chinese translation of John Howard Yoder’s The Politics of Jesus from 1988. They also discovered a Korean translation of an Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary leadership curriculum. Both were copy ready but may have never been printed.

They found dozens of resources on calling pastors, leadership-training programs and church-planting initiatives. While many of the initiatives didn’t necessarily last long, Jack says it was encouraging to be reminded of the church’s capacity. “These signals of a church very alive, a church that is creative and alive and energized,” he says. “It’s quite inspiring to see what all was tested.”

Irene says these valuable resources are languishing, neglected, when there is still so much of them that could be of use. “We only need to access them to help us understand where the conversations were then and how they can help us today in a very different context,” she says.

It’s also important to make this information accessible so that people, especially seniors, can access it for research and use it to document their own stories “and help us to make history come alive,” she adds. “Both of us really feel that we have so much to learn from what has been and how can that inspiration continue to guide us and shape us as a church.”

“We’re not only interested in what happened in the past, we’re interested in what’s happening now,” Jack says. “But very often what’s happening now can only be explained by what was. You can’t really understand what is happening now without seeing how we got there. That’s a key piece of archival work.”

After sorting and naming every file, the Sudermans will summarize the contents of each box, noting who created the material and why they did it. Stoesz will digitize that information and enter it into the MHA’s online system, so the material is searchable.

“We talk about how God is moving within congregations and within conferences, within people’s lives here and where mission workers are working,” Stoesz says. “We talk about how society has changed and the pressures on the church and denominations. Over time, those pressures change and that’s all reflected in those records. For the church, history is necessarily theology. By keeping this stuff we are documenting God’s work in the world.”

SEE LESS

This article appears in the Nov. 8, 2021 print issue of Canadian Mennonite, with the headline “Digging into the past.” Do you have a story idea about Mennonites in Manitoba? Send it to Nicolien Klassen-Wiebe at mb@canadianmennonite.org

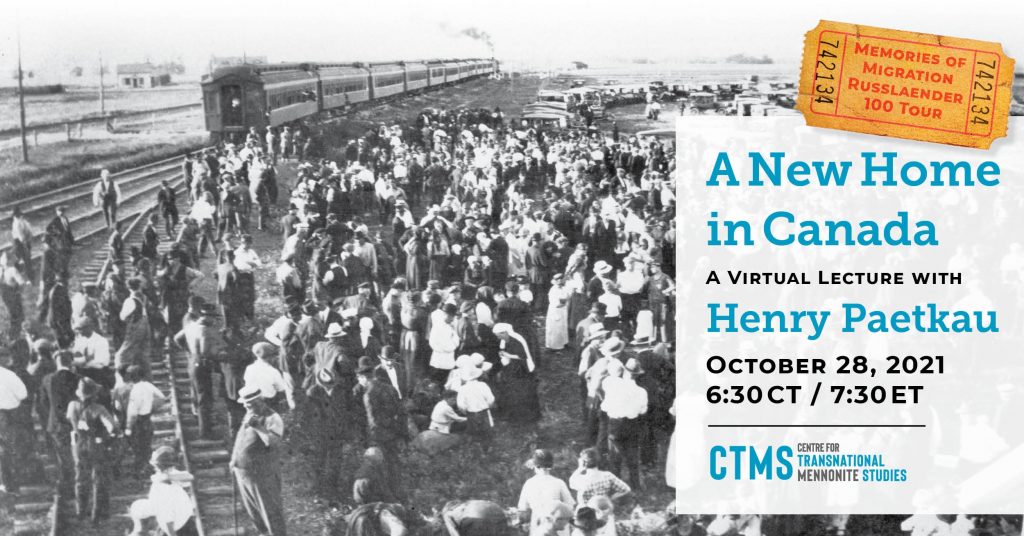

A New Home in Canada

A Virtual Lecture with Henry Paetkau

To learn about the historic 1923 migration of Mennonites from Russia to Canada, register for A New Home in Canada webinar with Henry Paetkau.

On October 28, 2021, 6:30 CT/7:30 ET, Henry will share the experiences of Mennonites as they arrived in Canada in the 1920s. Follow their journey as they find new homes, form new communities and meet their new neighbours. Discover the challenges they faced, the sorrows they suffered, and the faith that sustained their spirits. REGISTER ON ZOOM.

This webinar will give you a taste of the three-part Memories of Migration: Russlaender 100 Tour to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Mennonites migrating from Russia to Canada.

In collaboration with TourMagination, a company specializing in Anabaptist heritage tours, the Russlaender Centenary Committee has worked hard to develop this special cross-Canada train tour happening in July 2023. LEARN more about the Memories of Migration: Russlaender 100 Tour.

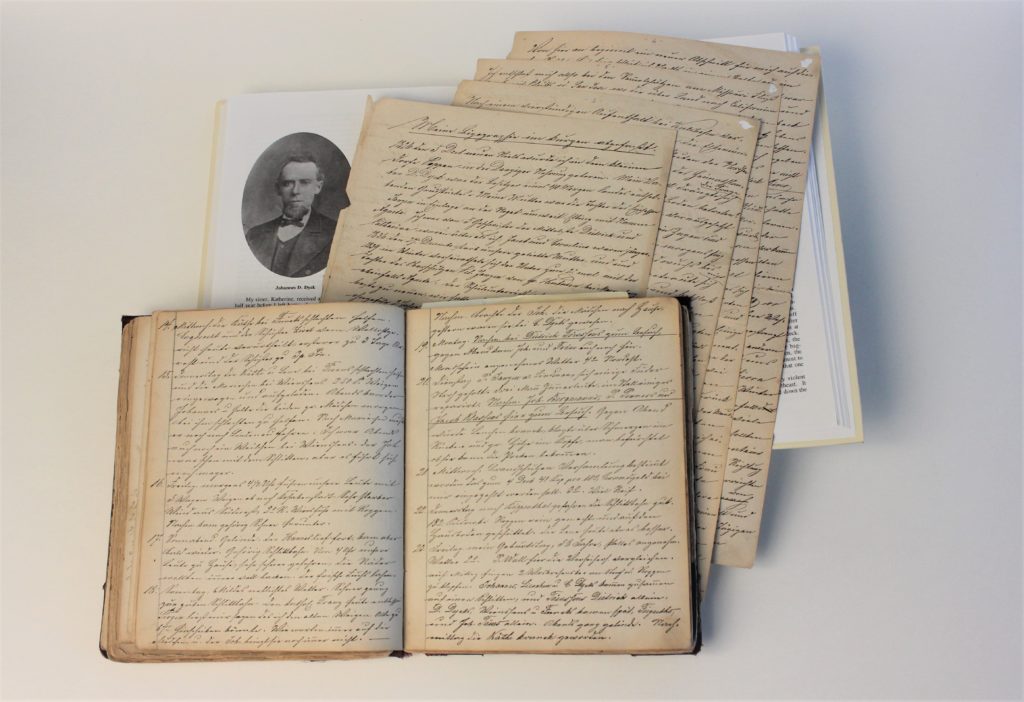

A New Look at an Old Diary

By Alf Redekopp, St. Catharines, Ontario

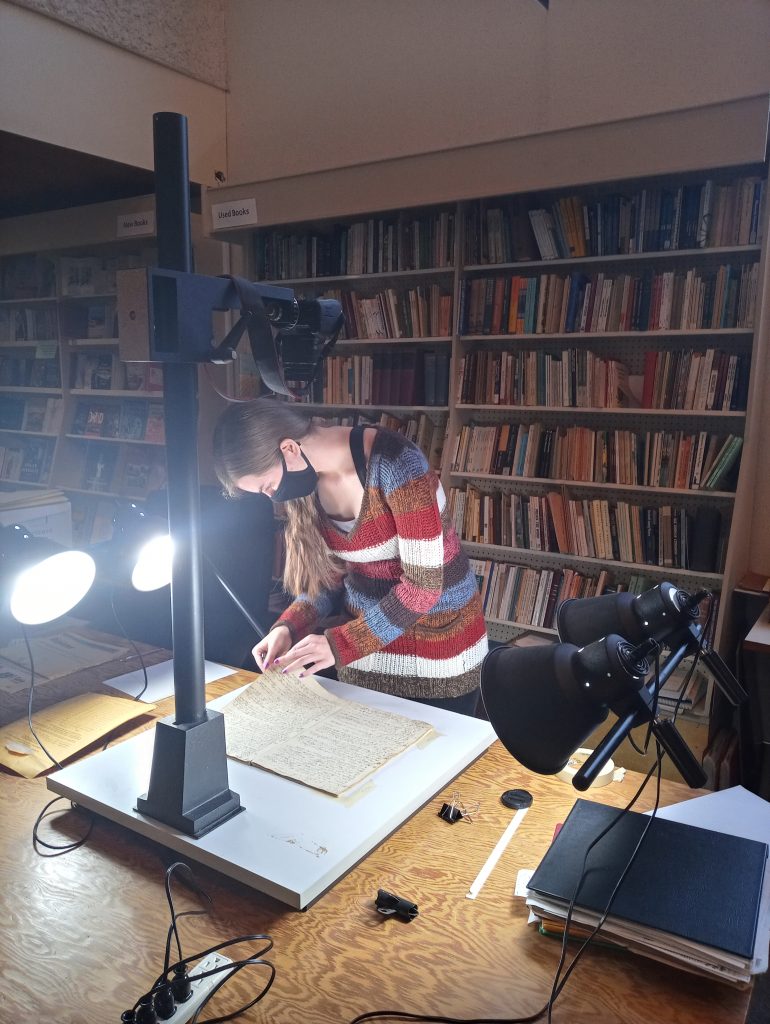

The diary of Johannes Dietrich Dyck was brought to the Mennonite Heritage Archives over 20 years ago. The donors were Dyck descendants who had used the materials to produce a family history, and as a final step in that process, they deposited some of that work and the key source documents in the archives. I was part of the archival staff that accessioned the material, created an inventory list, wrote a brief description, and transferred the diary for permanent safekeeping to the vault, where it would be preserved and accessible to future generations.

Johannes Dietrich Dyck is often distinguished in family folklore from other Johannes Dycks as “the 49er” because of his adventurous young adulthood. He left for America in 1848 to make his fortune in the 1849 California Gold Rush, returning 10 years later, marrying, and moving to the Am Trakt Settlement in Russia a year later in 1860. The diary was begun over a decade later in 1871, after he had established his farming operation and raised several children, but shortly before he was elected as the district civic administrator (Oberschulze). Johannes held that office for 18 years.

Excerpts from Johannes’s diary were translated and included in the family history book entitled A Pilgrim People, Volume II: Johannes J. Dyck, 1885–1948, Johannes J. Dyck, 1860–1920, Johannes D. Dyck, 1826–1898 (Winnipeg: George and Rena Kroeker, 1994). Additional family history can be found in Jacob J. Dyck, Am Trakt to America: A History and Genealogy, compiled by D. Frederick Dyck and others, published in 2000. The diary gives many glimpses into the rhythm of life in a late 19th-century eastern European agricultural community. One learns of the modes of transportation, the increased mechanization of agricultural practices, the impact of weather on farming, and the development of social welfare institutions, such as fire protection, crop insurance, and the welfare of widows and orphans.

SEE MORE

Little did I know when I first examined this diary 20+ years ago, that someday I would be asked to create an English translation; nor could I ever have imagined what I might find in the process.

Reading the diary closely now for the purpose of translation, so many years later, resulted in several discoveries that helped me make significant revisions to at least two biographies of 19th-century church leaders in GAMEO (Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online). Plus, I was able to add numerous birth, marriage, and death records to GRanDMA (Genealogical Registry and Database of Mennonite Ancestry) and make or renew friendships with like-minded genealogist/family historians during a period of physical and social restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alf Redekopp worked at the Mennonite Heritage Archives from 1994 to 2013. He retired to St. Catharines, Ontario, and continues to volunteer as a contributor/editor with several Mennonite research websites (GAMEO, GRanDMA, and MAID), as well as with the MHA in Winnipeg. Alf’s work on this diary can be found on the MHA website at https://www.mharchives.ca/publications/.

SEE LESS

‘The past always has something to say’

Manitoba Mennonites’ ancestors benefit from immunizations 200 years ago

By Brenda Suderman, faith reporter, Winnipeg Free Press

May 1, 2021

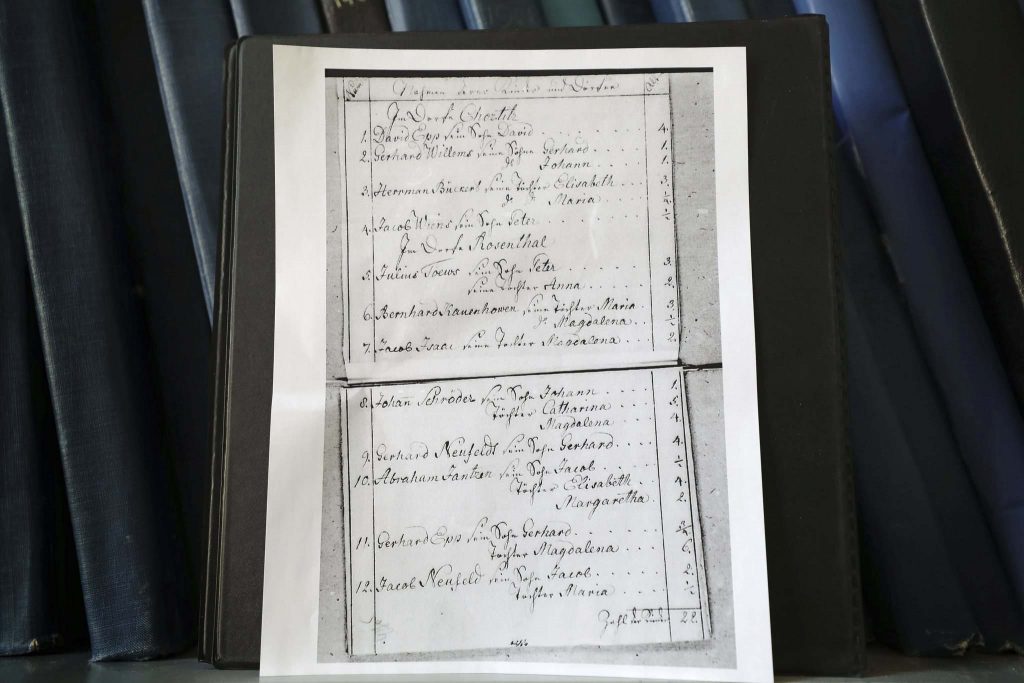

Photo of Conrad Stoesz, Mennonite Heritage Archives archivist, with microfilm of lists of Mennonite children innoculated against smallpox 200 years ago. Mennonite archivist Conrad Stoesz uncovers 200 year-old of Mennonite children who were innoculated against smallpox in Russia under an initiative by Catherine the Great, demonstrating that history has some lessons for current vaccination situation.

For a Winnipeg archivist, a bold move by an 18th-century Russian empress makes a strong case for people to get vaccinated during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Conrad Stoesz was reading about the efforts of Catherine the Great of Russia to protect her country against smallpox when he realized her connection to 200-year-old immunization records of Mennonite children held at Mennonite Heritage Archives at Canadian Mennonite University.

“I know people are discussing vaccinations and the safety of them and they’re wary of them,” says Stoesz, who has written about Catherine the Great’s immunization campaign in social media posts and German-language newspapers read by conservative Mennonite groups.

“Two hundred years ago people were trying out vaccinations and it works. Vaccines have shown to reduce illness.”

The 1809 and 1814 records lists names of about 400 children in the Chortitza and Molotschna Mennonite colonies, now part of the Ukraine, who were immunized against smallpox by medical personnel travelling from village to village, Stoesz says.

Descendants of those children were among the thousands of Mennonites who emigrated to Manitoba in the 1870s, including previous generations of Stoesz’s family.

“I might not be around today if some of (my) ancestors weren’t vaccinated,” he says of his personal connection to the two century-old lists, held on microfiche provided by Odessa Archives in Ukraine.

SEE MORE

Catherine the Great began a country-wide immunization effort against smallpox in 1768, after inviting British physician Thomas Dinsdale to use her and her son Paul as test subjects for an inoculation procedure that provoked a mild form of the disease in a healthy person.

English surgeon Edward Jenner had developed a smallpox vaccine derived from a pox-type virus related to smallpox in the late 18th century. Smallpox killed about 30 per cent of those infected, and often marked the recovered with deep pitted scars. In 1980, the World Health Organization declared that smallpox had been eradicated.

Printed copy from microfilm, of lists of Mennonite children innoculated against smallpox 200 years ago.

By 1800, about two million Russians had been vaccinated, and these Mennonite records demonstrate that the efforts continued into the 19th century, says an American family physician who transcribed the original records two decades ago.

“Our Mennonite ancestors were being pretty avant-garde and were starting to immunize their children against something very lethal at the time,” says Dr. Tim Janzen of Portland, Ore., who researches Mennonite history and genealogy in his spare time.

Like other families in Russia and around the world, Mennonites would have lost children to smallpox and may have been eager for their children to gain immunity, says Janzen, who fields questions daily from his patients about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.

Stoesz says the historical immunization lists offer some hope for our situation in the current global pandemic and set an example for some religious groups hesitant to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

“The past always has something to say,” he says.

“We just have to be looking for it and be attentive to it.”

Mennonites are encouraged to set another trend during this pandemic by lobbying Canadian politicians to donate excess vaccine supplies to other countries in need, says Anna Vogt, director of Mennonite Central Committee’s Ottawa office.

“The pandemic won’t stop anywhere until the pandemic stops everywhere,” she says of the reason for the campaign launched April 19 by the international relief and development organization.

Vogt says although Canadians have access to vaccinations in 2021, many others in the world don’t, and Canada has purchased more vaccine than it can use. MCC sent a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, federal cabinet ministers and opposition MPS asking them to create and implement a plan to redistribute excess Canadian vaccines to essential workers in low and middle income countries.

She encourages people of faith to send their own electronic message to political leaders by following the links at https://mcccanada.ca/get-involved/advocacy/campaigns/vaccine-justice.

“We’re really hoping Canadians of faith will join us in asking our government to do more in support of equitable vaccine access,” says Vogt.

SEE LESS

*The original article can be viewed on the Winnipeg Free Press website.

The Move to Mexico and Paraguay: A Call for Materials

The Mennonite Heritage Archives (MHA) is working with the Mennonite Heritage Village (MHV) in Steinbach, D.F. Plett Historical Research Foundation, and the Mennonite Historical Society of Canada in preparation for the commemoration of the movement of Mennonites from Canada to Mexico and Latin America in the 1920s. But we are looking for your help!

MHA is looking for archival materials that tell this story including oral interviews, photos, correspondence, diaries, and journals. MHV is looking for artifacts, which could include clothing, items relating to farm and home life, travel items, toys, or any other item with a story to tell that relates to the emigration of Mennonites from Canada to Latin America.

In the context of the First World War, the provincial governments of Manitoba and Saskatchewan wanted more compliant citizens. Officials believed they could instill more British values through the school system and, therefore, legislated that all children must attend government-run schools.

Some Mennonite groups complied with the new legislation, believing they could instill their values in other ways. However, other Mennonite groups resisted, believing education was the responsibility of the church and home, not the government. They pointed to the federal government’s 1873 letter of invitation explicitly offering freedom of religion and education.

The provincial governments also expropriated land for the new schools. If parents did not send their children to the government school, they were fined, imprisoned, and had their farm implements, livestock, and even food confiscated.

Between 1918 and 1925, there were over 5,500 prosecutions in Saskatchewan alone. In Manitoba, between 1917 and 1921, there were over $3,600 of fines collected from parents charged with not sending their children to the government-run schools. While the details of the larger story are documented, we lack individual stories revealing the struggle parents had in the education question, the impact of the fines on the family, the experience of having machinery or livestock confiscated. What was it like packing up the house and selling much of the household goods? Was the trip to Mexico exciting? What were the first months like in Mexico? These and other questions are being asked ahead of the 100th anniversary of this momentous migration.

SEE MORE

About 7,000 Mennonites left Canada in the 1920s, believing Canada had broken its promise (see the lead article in Mennonite Historian Volume 47, No. 1 March 2021). It was one of the largest movements out of the country since Canada’s confederation in 1867. These events have made an indelible mark on those who left, those who stayed, and on the countries they call home.

Some Mennonites who moved south were in dire straits because of the fines and travel costs. Even if they wanted to return to Canada, many did not have the means. Getting established in Mexico and Paraguay was difficult.

The move to Paraguay in 1926 saw 9.5% of the immigrants die by the end of 1928. But with hard work, ingenuity, and support from within the community, the

Mennonites were able to thrive. Today they are major economic players within their countries. But the scars of the government schools issue have left some with a longstanding suspicion of higher education.

The move to Mexico and Paraguay also changed the identity of the Mennonites who stayed in Canada. It is common for people to talk about “conservatives” and “liberals”; other rubrics use the terms “tradition-minded” and “assimilation-minded” as opposite ends of the continuum. The groups that left were the more tradition-minded, and they were in the majority in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Their views and values were the norm.

Not only did the more tradition-minded leave in the move to Mexico and Paraguay, their farms were taken up by some of the 20,000 Mennonites escaping hardship in Russia between 1923–1930. These new immigrants were related to those in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Mexico, and Paraguay, but 50 years of separation had resulted in many differences between the newly arrived Russländer and the Kanadier who started from scratch on the prairie in the 1870s.

Many who emigrated maintained ties with Canada, and in some cases citizenship, so that some of their children and grandchildren have returned to Canada.

SEE LESS

This story has themes related to justice, immigration, education, and multiculturalism. If you have materials that could help tell this story, please be in touch with Conrad Stoesz at the Mennonite Heritage Archives (cstoesz@mharchives.ca) or Andrea Klassen at the Mennonite Heritage Village (andreak@mhv.ca).

New MCC Archivist

By Conrad Stoesz

There is a new Mennonite archivist in town! Andrew Klassen Brown began his role as Records Manager and Archivist at Mennonite Central Committee Canada at the beginning of December 2020. A series of short-term church and archival jobs have helped him prepare for this new role. Klassen Brows says that “I seem to have stumbled upon the Mennonite archiving community almost by accident.”

In 2016, Klassen Brown graduated from Canadian Mennonite University (CMU) and was chosen by the Mennonite Brethren Historical Commission for the Archival Internship program. He spent of five weeks visiting each of the Mennonite Brethren archival Centres in North America (Fresno, Hillsboro, Winnipeg, and Abbotsford) during the months of May and June. His tasks included scanning images, keeping a blog, compiling information on the theme of migration, and entering data into the Mennonite Archival Information Database. During this time Klassen Brown had moved his career goal away from becoming a high school teacher and enrolled in a master’s degree at CMU in Theology and History.

In the summer of 2017 Andrew landed a term position at the Centre for Mennonite Brethren Studies funded by the Young Canada Works program. Under the supervision of Director Jon Isaak, Klassen Brown developed his skills around archival arrangement and description. From 2018-2019, Klassen Brown was the executive assistant at Mennonite Church Canada where he put his organizational skills to good use. Through the denomination’s transition to a smaller organization, there was a lot of sorting out that needed to be done.

SEE MORE

In the spring and summer of 2020, he worked for the Mennonite Heritage Archives thanks to funding from the Young Canada Works program. Andrew organized and described a number of congregational records from Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Because of the pandemic this work was mostly accomplished at home but with daily check ins via zoom with archivist Conrad Stoesz. For many of the congregations he also wrote Facebook posts. This task encouraged deeper thinking about the records he was working with, the congregation, its context and the people who were part of that community. It led to long discussions about the church, community, urban, rural, and conservative, liberal, and changing values. The social media posts he created were well received with an average of 7000 views for each post. According to Klassen Brown “working with Mennonite archives has not only been a job for me but has also connected me to people in my community, allowed me to learn more about my faith, and has paired well alongside my academic work throughout my studies.”

Andrew continues to be involved with the Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society. He plans on graduating with a MA from CMU in Spring 2021. His thesis explores the connections between apocalyptic expectation and peace theology in the sixteenth century, using Clemens Adler and Menno Simons as case studies.

Andrew is excited to be in this new role with MCC. “My hope for this role is that I can make the stories of the good work that MCC does around the world and in our backyard accessible to inspire people in the present and future to continue the vital ministries of relief, development, and peace in the name of Christ.

SEE LESS

Royden Loewen: Farmer, Historian, Storyteller

Interview conducted by Robb Nickel

Newly minted retiree, Royden Loewen grew up on a farm near Blumenort, East Reserve, southern Manitoba. I knew there was a guy named Royden Loewen who taught Mennonite history at the University of Winnipeg (UW), but I really got to know him when he and Mary Ann (his partner) began attending Fort Garry Mennonite Fellowship. He became more than a historian, I saw him in the role of father, grandfather, friend, avid reader and willing volunteer when it came to church assignments. I also got to know the farmer who parked his red pickup truck on the driveway beside the Red River at his home across the river from mine. Conrad Stoesz, archivist at the Mennonite Heritage Archives presented me with the privilege of interviewing Royden and hopefully, the following questions and answers will shed a light on who this man is…

Robb: First, tell me a bit about your background, childhood, growing up in the Kleine Gemeinde Church near Steinbach, something about the experience of having grandparents who moved to Mexico, what led you to the study of Mennonite History and acquiring a Ph.D.

Royden: I recall the Blumenort EMC church (formerly Kleine Gemeinde) when it still had its German Sunday, no piano, the pastor (my uncle John) without a tie, my older sisters chastised for not wearing head coverings; all that changed in my youth, but I nevertheless witnessed it, and knew about the plain people part of my history. My own grandparents, Isaac and Maria Loewen, moved to Mexico in 1950 with most of my uncles and aunts, and I have been to Mexico in every decade of my life – that Mexico connection and that we had not moved was part my identity. My father was the rebel – the true evangelical Christian does not run from the world – he doubled down to make sure we would assimilate; he expanded the farm and sold the cows, pigs and horses and specialized in poultry, my mother dressed to the nines, we children were not allowed to speak Low German, dad would have been so pleased if we had all married non-Mennonites and non-white Mennonites at that! I rebelled by studying Mennonite history and marrying a Mennonite! About Mennonite history: I had other interests – politics, law, geography – but I consistently obtained my best marks in history, and my first-year history prof at MBBC, Dr. George Epp, had me spell bound in the first year Western Civ. course. I honed my teaching (and my worldview) at Fisher River First Nation where I taught from age 24 to 26, and there found deep satisfaction in adding Indigenous history to the high school curriculum, at the very time that I was invited to write a history of my home community of Blumenort; the exercise of these two initiatives both rested in the idea of creating narratives for ‘people without history’, to allude to Eric Wolf’s classic by that title. Mennonite history was my narrative and Blumenort became my MA thesis, and a history of the Kleine Gemeinde, my people, in Nebraska and Manitoba, became my PhD dissertation; my newest book, in press right now at Johns Hopkins University Press, and based on the Seven Points on Earth project – an environmental history of seven Mennonite farm communities from around the world – is merely the offspring of a life-time interest in creating narratives for people, and the Mennonites are my people.

SEE MORE

Robb: How did the Chair in Mennonite Studies at the UW become yours? What was the program like when you took over, how has it changed under your leadership and where do you see it going after you leave?

Royden: Well, I applied for it and this is the job I got; within the month of being interviewed for the Mennonite Studies position I was also interviewed for Canadian history at the University of Washington at Bellingham, and before that for positions in Ethnic Studies at University of Calgary, Canadian history at Isaac Brock in St. Catharines, and there were a number of other possibilities; so, it must have been destiny! I think the timing was good: in 1996 I had just completed a stint as Fulbright Fellow at the University of Chicago, my first university press book had won some nice awards, so I think I had somehow come onto the radar of the folks at UW; it didn’t hurt that Dr. Harry Loewen, the Chair in Mennonite Studies at the time asked me to give the fall public Mennonite Studies lecture at UW the year before in 1995 and the lectures were on the history of gender, which was a new turn in a sense in Mennonite Studies which had had a more literary and theological focus. My answer to this question I think will be fleshed out in answers to questions below.

Robb: What are some of the changes you have seen in the field called Mennonite Studies? Also, how is your work integrated with the work being done at the Mennonite Heritage Archives?

Royden: I think the big changes come with changes in leadership: my predecessor Dr. Harry Loewen was an expert in Reformation Studies and German Literature, and my own was in Canadian Social History, and my successor is an expert in yet another subfield of Mennonites. So the changes of note are those at the nexuses of generational succession. My own interests have changed somewhat – perhaps from issues of ethnoreligious identity to those of power and nature – but at the foundation they have always been with the everyday expressions of culture and faith, with seeking to understand how people put their local worlds together. Thus, my abiding interest and the things I have written about, relate to everyday religion, gender relations, generational succession (inheritance, mythology, lore, personal narratives such a diaries and memoir). At heart I think I’m an anthropologist, I wonder about how people order their worlds in the chaos of life and create symbols of meaning. The Mennonite Heritage Archives is crucial in these pursuits: historians can only write about stuff they can know about; I have chatted with Conrad Stoesz, and before him Lawrence Klippenstein, and the other directors, on a regular basis over the years; the role of the archivist is an absolutely crucial role for any community; the archivist is the custodian of the record of knowledge; the historian’s job is to interpret and mobilize that knowledge.

Robb: List a few of your major accomplishments as Chair of Mennonite Studies.

Royden: I would rather answer this question with regard to what were my most satisfying activities, and they were numerous: I loved editing the Journal of Mennonite Studies and working with the some 300 individuals who published in it over the 24 years I was editor; I enjoyed developing new courses, (and to the final year, gained satisfaction in developing an Indigenous-Mennonite relations course that I never got to teach); I have always found peace in the act of writing and much enjoyed putting together a variety of history narratives in book form; I gained a great deal of satisfaction in working with various groups of scholars in creating and delivering on the annual (October usually) Mennonite Studies conferences; I loved teaching at all levels and rousing the curiosity of Mennonite history in students; I enjoyed working on the bones of the Centre for Transnational Mennonite Studies (CTMS), negotiating with UW administration; I felt great satisfaction in working with colleagues and they are too numerous to enumerate, but Hans Werner, Andrea Dyck and I were for a long time a team at CTMS, and in more recent years it was Aileen Friesen and Jeremy Wiebe; even the process of working at handing off to Ben Nobbs-Thiessen, my successor, was satisfying.

Robb: Has the interest in Mennonite Studies grown during your tenure, have the students changed and has there been an increase in interest in this field?

Royden: For sure: class size has grown steadily; remarkably Mennonite Studies I and II, our second-year foundation courses, easily compete in size with other history or religious studies courses at UW, and graduate students wishing supervision in some aspect of Mennonite history have been there in respectable numbers as well. The students themselves were similar somehow over the 24 years I served as Chair: oftentimes I thought, they were 1/3 practicing Mennonites, 1/3 near Mennonites (they were dating a Mennonite, their grandmother was a Mennonite, they somehow had fallen in love with Mennonites) and then 1/3 who had no clue about Mennonites or Christianity or Protestantism, but needed a history or religious studies credit; one student once told me that C.J. Dyck’s Introduction to Mennonite History was a lot less expensive than the textbook required for the first year biology course he was also considering, so, of course, he enrolled in Mennonite Studies. My greatest satisfaction came from making Mennonite history come alive for each of these student cohorts.

Robb: What are some of the challenges you have worked at and see for the future of Mennonite Studies? Is there adequate funding for this kind of program?

Royden: One of the main preoccupations in the last years at UW was to create the Centre for Transnational Mennonite Studies (linking the Chair in Mennonite Studies formally with the D.F. Plett Historical Research Foundation) and seeing it continue from the place that Hans Werner and I had taken it to. Getting the UW administration to agree to fill Hans’s position as Mennonite historian and ED of Plett and finding that person in Dr. Aileen Friesen, a gifted specialist in Russian Mennonite history and then my own position ultimately with Dr. Ben Nobbs-Thiessen, an equally gifted specialist in Latin American Mennonites from an environmental history perspective, was a bit of work. The future of the program is in their hands now; and given that we have a specialist in Canadian Mennonite history, Jeremy Wiebe, working as the Centre’s financial and communications officer, rounds out a dynamic team of young scholars. And without going into details, the CTMS at UW is very well-funded, with generous support from a range of donors, beginning with a very substantive gift back in 1978 from David and Katherine Friesen of Qualico Homes, the Federal Government, the UW itself, and from a host of more recent donors, all allowing for endowments to undergird every aspect of its program: and with possibilities of growth in the future, and collaboration with other institutions, such as Canadian Mennonite University.

Robb: What are some of the important lessons you have learned over the years about education, about Mennonites, about yourself and the community you choose to be a part of?

Royden: Education is to know yourself within a wider context, to build an identity, to learn how you are rooted in that context. History is story that makes you who you are. I am never bored talking to anyone, that is, if they allow me into their stories. Every person has a story that is complex, consequential, compelling. And I have my own story: I talk easily about my grandparents moving to Mexico and my grandfather Isaac Loewen opening an English language book store once he got there; I grew up in a happy home, was close to my father, respected him, came to know my mother well after my dad died, hearing her stories of growing up in very poor circumstances; I admired their commitment to non-violence. My world expanded at MBBC which in the 1970s had discovered and embraced the ‘Anabaptist Vision’ as well as critical thinking. I found in Mary Ann a soulmate and we have travelled a parallel intellectual pilgrimage of finding meaning in a poetics of faith, and locating ourselves within community, in the various church communities we have been members of or even churches we have attended fleetingly on our various sabbaticals – Chicago, Victoria BC, Guelph/KW, Cambridge (England), Santa Cruz (Bolivia) – it’s been humbling and life-giving and redemptive.

Robb: How do you feel about leaving your “post” and what are you going to pursue in retirement? Maybe share a bit about your farming, organic and all.

Royden: I feel really good about leaving with a Centre in place with talented, energetic, committed young scholars; I have told both Aileen and Ben that I will gain a great deal of pleasure watching to see how they grow and develop the CTMS program. I’m not easily given to sit back (for better or worse) and will be doing things: I have two lovely grandchildren – Remy and Kay – who live a 10 minute bike ride from our house, I talk to each of my own children – Becky, Meg and Sasha – regularly and often, and am challenged by their own aspirations and the big questions they ask. I love being with Mary Ann (cycling, talking, drinking coffee, planning). We have a large garden and a dozen chickens at Millview, our acreage near Steinbach. I still serve on too many Mennonite history committees and boards. And there is our Millview Grain Inc, a certified organic farm from which I gain a great deal of satisfaction – organic ag is more work and more involved but much more interesting to me than conventional or chemical-based farming; just this last week I had multiple phone calls with Alden Braul from BC regarding alfalfa seed sales, a rep from Harvest Manitoba regarding hemp sales, an organic wheat purchaser from Quebec, crops we grew on the farm this year, all now safely tucked away in granaries. And I look forward to final fall tillage, preparing the seed bed for next year, tending to drainage and fertility; and building on this I serve on the Manitoba Organic Alliance board. Of immense importance, my partner on our farm is our son Sasha, who is studying agriculture in Montana and using our farm program as part of his dissertation. And then too, there is the new Transnational Flows of Agriculture Knowledge (TFOAK) research program that is well funded with a multi-year SSHRC Insight Grant, and sees a team of students analyze everything Mennonite about this intellectual problem – how does agricultural knowledge envelope itself with power and within an international context.

Robb: Give me a final word, perhaps about what gave you the most joy in your Mennonite Studies work.

Royden: There was a lot of joy: to help provide people with a story of who they are: to teach Mennonite Studies I (i.e. Anabaptist history) to students of Mennonite descent or even practicing Mennonite, but who were unaware of the rich and varied history of the Anabaptists – the politicized vision of the authors of the Schleitheim confession, the remarkable women, the odd mystics, the passion of Menno Simons, even the nasty Anabaptists; to explore Mennonite history in all its iterations, especially apparent to me in the annual Mennonite Studies; to see the Anabaptist hermeneutic work its way out in the various themes of the 25 conferences I had the privilege to work on – regarding Mennonites and money, mental health, literature, Indigenous-Mennonite relations, technology, pacifism, anthropology. I come back to helping people find stories that root them and tend to their curiosities of who they are and who their neighbours are.

Robb: Thank you, very much, Royden, for providing interesting and thoughtful answers to my questions. May God go with you in retirement, as you seek to serve God in the many endeavours you have shared with us.

SEE LESS

Mennonite Heritage Archives part of groundbreaking storytelling project

Thursday, November 12, 2020

When we think of preserving history in archives, our first thoughts might be of digging through boxes of grandma’s things in the attic or leafing through yellowing photo albums. But that is not the whole picture.

The Mennonite Heritage Archives (MHA), located on CMU’s campus and supported by CMU, is calling on Mennonites and Anabaptists to share their experiences during the remarkable historical, biological, and social events of 2020 as part of Anabaptist History Today (AHT), a groundbreaking collaborative storytelling project.

AHT was launched in the summer of 2020 and is the first large-scale, collaborative digital project of its kind in the Anabaptist community. The MHA is one of sixteen North American Anabaptist archives and history organizations participating in the project, led by Mennonite Church USA Archives and Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society.

It can often take decades for stories to reach the archives, but AHT is using crowdsourcing to capture history being made right now, from COVID-19 to the Black Lives Matter movement to climate change. The online form that guides people through uploading their contributions is easy to use and empowers the average person to create a lasting record that will be stored in the archives.

SEE MORE

The MHA invites individuals, congregations, schools, and organizations to tell their stories of living during these changing times. Contributors can share their experiences through a variety of media, including videos, audio recordings, photos, journal entries, artwork, poetry, and personal reflections.

At the time of this article’s publication, 33 records had been submitted to the project so far. Conrad Stoesz, Archivist at the MHA, hopes the website will continue to receive more contributions to get a broad perspective of how Mennonites are experiencing life during these unprecedented times.

Stoesz has already entered multiple submissions, including two photos of CMU from March 2020. One shows an empty Marpeck Commons, with tables spread far apart and a lone chair seated at each table. The other depicts the CMU chapel set up for physical distancing in preparation for a staff gathering.

He hopes the AHT project will raise awareness about the important work heritage institutions continue to do in our world today. To learn more, visit https://aht.libraryhost.com/s/archive/page/Welcome.

SEE LESS

*This article was originally published on CMU’s Media Centre Stories page.

Interested in more?

More stories can be found by following the FEATURES tab in the menu bar of this website to the STORIES page.